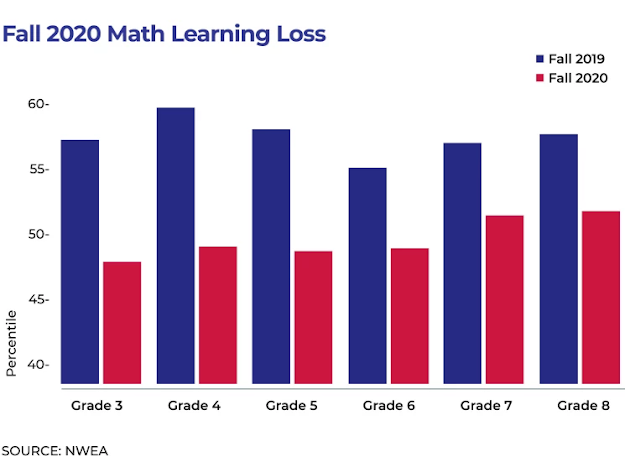

COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime. Learning Loss in Math reaches average up to 60% which is equal to 3 Months of Learning Loss

New evidence shows that the shutdowns caused by COVID-19 could exacerbate existing achievement gaps. The US education system was not built to deal with extended shutdowns like those imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Teachers, administrators, and parents have worked hard to keep learning alive; nevertheless, these efforts are not likely to provide the quality of education that’s delivered in the classroom.

A sweeping new review of national test data suggests the pandemic-driven jump to online learning has had little impact on children's reading growth and has only somewhat slowed gains in math. That news comes from the testing nonprofit NWEA and covers nearly 4.4 million U.S. students in grades three through eight. But the report also includes a worrying caveat: Many of the nation's most vulnerable students are missing from the data.

"Preliminary fall data suggests that, on average, students are faring better than we had feared," says Beth Tarasawa, head of research at NWEA, in a news release accompanying the report.

Of the students in grades K-7 who were tested in 2019, Kuhfeld and her colleagues found 1 in 4 did not get tested this fall, across grades in reading and in math. Likewise, schools with higher poverty were less likely to participate in the test, which could skew the overall results.

Learning Loss and School Closures

To that end, we created statistical models to estimate the potential impact of school closures on learning. The models were based on academic studies of the effectiveness of remote learning relative to traditional classroom instruction for three different kinds of students. We then evaluated this information in the context of three different epidemiological scenarios.

For simplicity’s sake, we have grouped high-school students into three archetypes. First, there are students who experience average-quality remote learning; this group continues to progress, but at a slower pace than if they had remained in school.4 Second, some students are getting lower-quality remote learning; they are generally stagnating at their current grade levels. Then there are students who are not getting any instruction at all; they are probably losing significant ground. Finally, some students drop out of high school altogether.

We also modeled three epidemiological scenarios.

In the first—“virus contained”—in-class instruction resumes in fall 2020.

In the second—“virus resurgence”— school closures and part-time schedules continue intermittently through the 2020–21 school year, and in-school instruction does not fully resume before January 2021 In the third scenario—“pandemic escalation”—the virus is not controlled until vaccines are available, and schools operate remotely for the entire 2020–21 school year.

Most studies have found that full-time online learning does not deliver the academic results of in-class instruction.

Significant numbers of students appear to be unaccounted for. In short, the hastily assembled online education currently available is likely to be both less effective, in general, than traditional schooling and to reach fewer students as well.

On average, that means students lost the equivalent of three months of learning in mathematics and one-and-a-half months of learning in reading.

The learning loss was especially acute in schools that predominantly serve students of color, where scores were 60 percent of the historical average in math and 77 percent in reading

(Exhibit 1).

These results are only a snapshot of a small cross section of students, but, if anything, these students may outperform national averages. These assessments were taken in school by students who had already made it back into the classroom.

The reality is that the 2020–21 school year is going to remain a challenge for every student. The COVID-19 pandemic has upended the US education system, forcing schools to adopt strategies without certainty about the results.

There are no rigorous studies on the impact of hybrid models—not just on learning, but also on students’ emotional and mental health, as well as on limiting disease spread. This makes it tough for schools to design effective learning strategies and makes it difficult for researchers to predict the impact of ongoing disruptions.

Guided by pre-COVID-19 studies of the effectiveness of virtual learning and by assessment data collected at the start of this school year, we created four scenarios to consider:

- No progress. As a baseline scenario, this is what students were on track to lose had we continued on the same path as the initial switch to remote learning in the spring.14 Given the improvements this fall, we hope we have averted this worst-case scenario.

- Status quo. This presumes that students stay in their current learning modalities (remote, hybrid, or in-person) until the end of the school year, with a mix of remote learning quality slightly better than historical virtual charter school performance.

- Better remote. In this scenario, students stay in their current learning modalities until the end of the school year, but with significant improvements in remote and hybrid learning quality.

- Back to school. This scenario is identical to the status quo scenario to the end of 2020, and then students resume a more typical in-person schedule from January 2021 to the end of the school year.17

The results are startling. Students on average could lose five to nine months of learning by the end of June 2021. Students of color could be six to 12 months behind, compared with four to eight months for white students (Exhibit 6).

All of these scenarios will have a meaningful impact on existing achievement gaps, but shortening the length of disruption or improving the quality of remote learning can lessen this impact significantly, especially for students of color.

Learning loss will probably be greatest among low-income, black, and Hispanic students. Lower-income students are less likely to have access to high-quality remote learning or to a conducive learning environment

And this could be just the beginning—we also know from studies of natural disasters, that learning losses are likely to compound over time. Schools can take action right now to minimize further damage and repair what’s already been done.

AUTHOR(S)

Cory Turner from NPR,

Sarah Sparks from edweek,

Emma Dorn is the global education practice manager in McKinsey’s;

Bryan Hancock and Jimmy Sarakatsannis; and Ellen Viruleg senior Advisor.

Source and References -

Comments

Post a Comment